Chapter 5: Social media, technology & innovation

THE STUDY

Chapter 5: Social media, technology & innovation

Digital native media organizations in our 2016 study were heavy users of social media for the distribution of their content, and many developed substantial followings. Our analysis shows similar findings for this study.

More than 90% of the sites in our global sample reported using Facebook and Twitter, more than 80% used Instagram, and around 70% used YouTube. Around 27% used LinkedIn, and 10% used TikTok. Notably, just two organizations reported using Snapchat in this study.

Changes since our 2016 study include a drop in Snapchat use; 6% of organizations in Latin America reported using this three years ago.

In contrast, Instagram in Latin America has grown from 62% to 96% since our first study.

Digital native media reach millions via social media

Social media audiences vary widely among these media, but many have attracted millions of followers and rely heavily on social platforms to distribute their content and engage with their community of readers.

Malaysiakini in Malaysia, for example, which publishes in multiple languages, has 1.4 million followers across its English and Malay Twitter profiles, and 5.2 million Facebook followers across its English, Malay, and Chinese Facebook pages. IDN Times in Indonesia has more than 2 million followers on Instagram.

In Mexico, Sopitas, which covers news, sports, and entertainment, has more than 3 million Twitter followers.

Ghana’s Ameyaw Debrah, a one-person newsroom covering world news, culture, arts, and entertainment, has 1.2 million Twitter followers.

However, the number of followers varies widely across the media in this study. The average number of Facebook followers was 148,829, for Twitter it was 115,549, for Instagram 53,411, and for YouTube 48,818.

Social media is an important distribution channel for many of these media and helps them extend their reach to audiences they may not find through other channels. We saw many examples of sites using social media in truly innovative ways.

ConexiónMigrante in Mexico, for example, responds to voice messages sent through Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp to reach the most vulnerable and sometimes illiterate members of their audience.

And a few of the media in this study publish only on social media. In South Africa, Hashtag Our Stories uses Snapchat as its main distribution channel, while The Continent shares its digital newspaper almost exclusively via WhatsApp.

Nearly 25% of the sites we interviewed sell social media mentions or sponsorship in their posts, although this figure was slightly lower in Africa, where only 15% of media organizations said they earned revenue this way on social platforms.

Although our research suggests that building a website, instead of relying solely on social media, provides more revenue opportunities, we’ve also found that media leaders with limited resources sometimes find it easier (and more affordable) to get started on social media.

Animal Político started as a Twitter account under the name Pájaro Político before launching their website in 2010. Today, they are widely recognized as one of the most influential digital media news sites in Mexico with millions of readers.

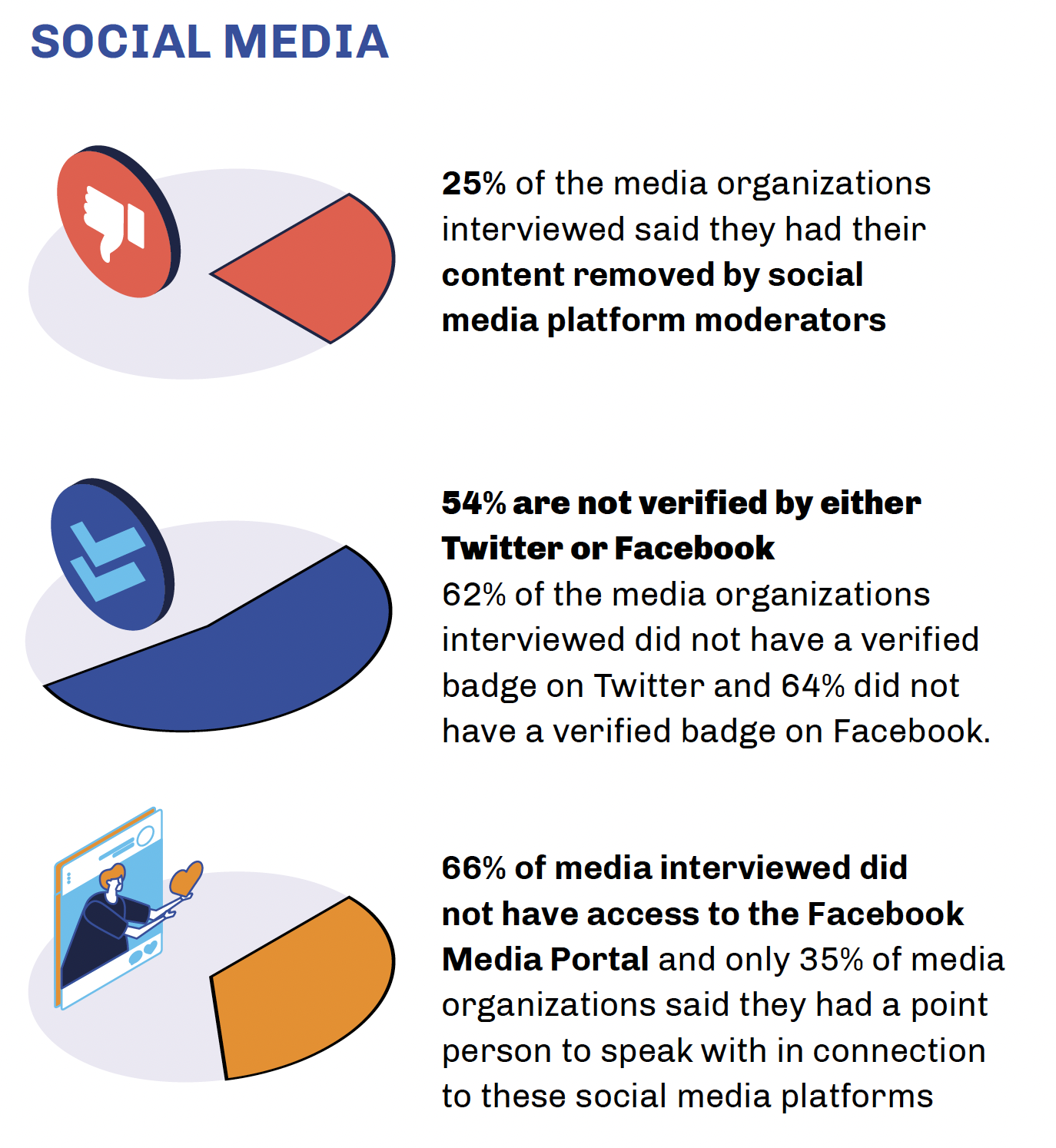

Social media shutdowns are hard to appeal

There is an inherent risk in relinquishing control over your relationship with your audience to social media platforms.

Because so many of the media organizations in this study rely on social media platforms for traffic, audience engagement, and more—having a profile taken down can have devastating effects on their traffic and journalistic impact.

In conversations with media leaders, we’ve heard first-hand reports about YouTube channels being closed because coverage of violent events was perceived to violate policies or because political leaders falsely accused them of copyright violations when they used images in the public domain.

When profiles are taken down, digital native leaders said they have had to reach out to social media platforms to appeal the suspension/ban and get back online.

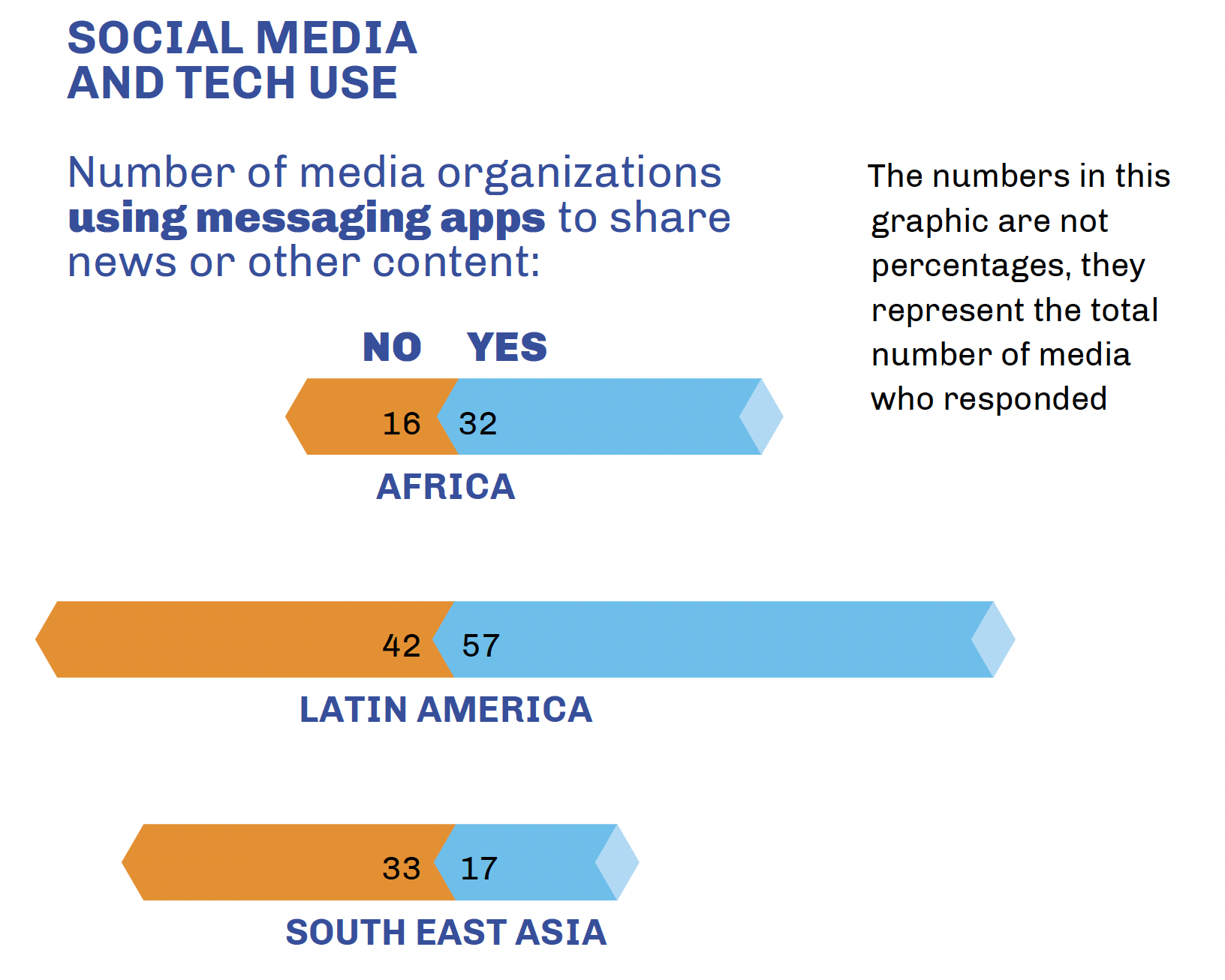

Messaging apps provide important distribution channels

The growth of messaging apps, and their use for spreading misinformation, has been well documented in recent years, making it an important platform, especially for media that specialize in fact-checking.

More than half of the digital media leaders we interviewed said they used messaging apps to share content. In Africa, this figure was 66%, in Latin America it was 57%, and in Southeast Asia 34%.

This is a notable change from our first Inflection Point report. Less than 12% of the media we interviewed in Latin America were using WhatsApp in 2016.

WhatsApp, which is owned by Facebook, was by far the most popular messaging app among media in Latin America and Africa, where it’s used to share breaking news updates as well as facilitate conversations with audience members.

In Southeast Asia, the top messaging app cited in our interviews was LINE, which is owned by a consolidated subsidiary of South Korean Internet giant Naver and SoftBank Corp.

Telegram, which was developed by a Germany-based tech company called Durov Software Industry, was the second most popular app overall. Similar to WhatsApp, it was used by media in all three regions, although at a much lower rate.

As highlighted by Laura Oliver’s research for Reuters Institute on publishers’ use of messaging apps in Zimbabwe, Brazil, and South Africa, there are concerns from some publishers about the drawbacks of messaging apps, and particularly WhatsApp. These include WhatsApp’s group size limits and nervousness about data privacy.

There is considerable evidence that Telegram is growing in popularity, largely because it is perceived to offer better security features and because it can support up to 200,000 members per group chat, while WhatsApp allows only 256.

Other messaging apps used by organizations in our sample included Signal, Slack, Discord, Facebook Messenger, and Viber.

Technology and innovation drive revenue

The news organizations in this study were born on the Internet, so tech is at their very heart—central to how they distribute their journalism and how they interact with their audiences.

How they use tech also impacts their bottom line. Across all three regions, our analysis found that news organizations with a paid employee in charge of tech innovation had three times more revenue than those who did not, even when they did not have a dedicated sales person on the team.

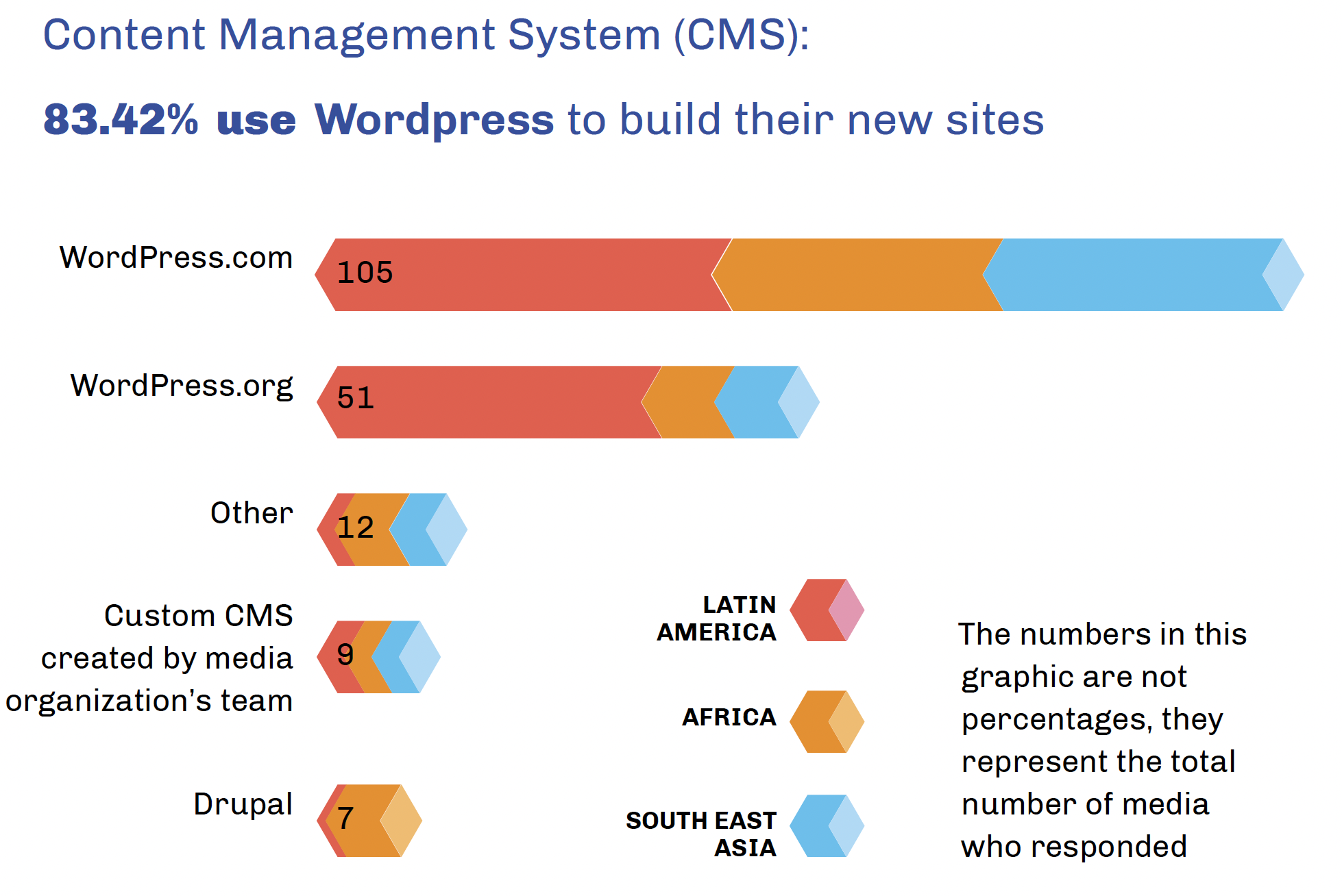

WordPress is by far the most popular Content Management System

Nearly 85% of 200+ media interviewed for this study built their websites with WordPress, a finding that was consistent across all three regions. To put that number in perspective, Automattic, the company that created WordPress, boasts that 42% of all of the world’s websites are built with their CMS.

WordPress comes in two flavors:

WordPress.com

Automattic hosts WordPress.com sites—the commercial version of its CMS—on its own servers and charges publishers to use it. This version rules as the top CMS and is used by 56% of the sites we studied. Although WordPress.com does offer a free level of service, the cost of customizations, from special templates to plugins, can add up quickly, and at the highest levels of support, costs can reach tens of thousands of dollars per month. This has led foundations like the Knight Foundation to create tech stacks, custom news themes, and other solutions that they recommend, and even sponsor, for grantees.

WordPress.org

In contrast, the open-source version available at WordPress.org is free. It’s even frequently included as a “One-Click Install” in the standard packages of most private web hosting services, such as GoDaddy, GreenGeeks, and DreamHost. In addition to the lower initial cost, the open-source version offers the greatest amount of customization options. The trade-off is that it requires its users to manage all the tech development and maintenance themselves, which may open them up to greater risks of digital attacks, as well as website crashes. This version of WordPress is used by 27% of the sites we studied.

With such low annual revenue, most of the media in this study simply can’t afford the technical products and services that are commonly used by larger media organizations and those in wealthier countries.

For example, Newspack, a joint project of WordPress.com and the Google News Initiative, “is designed to serve the needs of small and medium-sized digital news publishers by sparing them the burden of developing and maintaining their own tech stack,” according to the website.

Pricing is based on annual revenue, and according to the site, “Prices generally fall between 2.5 and 5 percent of a publisher’s annual revenue.” But the lowest annual revenue they use to set pricing is $250,000 a year—far more than the revenue generated by the vast majority of digital native media in the countries we studied. Even at their lowest price level, Newspack costs $500 per site per month, making it prohibitively expensive for the media in this study.

Although there is a free, open source version of Newspack, you need an experienced WordPress developer to set it up. Many media leaders we’ve spoken with in our training and acceleration programs said they didn’t even know there was an alternative to the premium service and had simply decided they couldn’t use Newspack because it’s too expensive.

We don’t mean to single out WordPress or NewsPack—the high cost of other technology solutions is a burden for these media as well—but our finding that the majority of the digital native media in this study are using the more expensive version of WordPress makes this an especially important tech category.

Limits of online payment systems restrict revenue opportunities

Despite a surge in online transactions during the pandemic, the relatively low use of credit cards and commercial banks in the countries we studied restricts how many of these media earn revenue through online sales.

According to the Global Payments Report by FIS, a financial services company, global e-commerce spending increased by 19% from 2019 to 2020, an increase that usually takes two to three years. Overall, $4.6 trillion was spent in e-commerce transactions in 2020. By 2024, it’s expected to grow to $7.3 trillion.

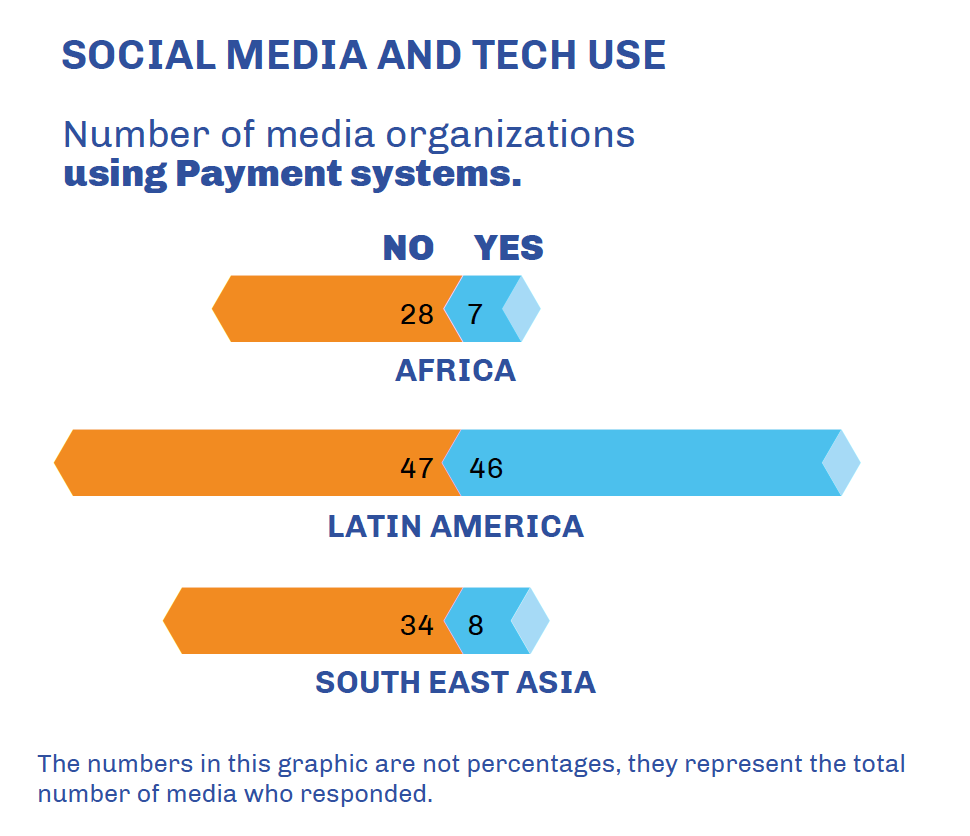

Yet less than 30% of the media leaders we interviewed reported using any sort of online payment system, a vital requirement for selling subscriptions, memberships, or products online.

HumAngle in Nigeria said it was developing a paywall for some stories and planned to launch a membership program, but had halted development because of the challenges of setting up a reliable payments system.

The lack of trust among consumers can also make reader revenue strategies difficult to get off the ground.

HumAngle also reported that audiences outside of Nigeria did not want to make payments via a Nigerian IP address because of security concerns and that setting up an international bank account outside of Nigeria to get around this problem had proven prohibitively challenging.

So many payment systems, so few real solutions

We found 32 different types of payment systems being used by the media in the 12 countries included in this report. Yet even those who have found a way to set up these services said significant portions of their audience lack the types of credit cards or banks required to use them.

PayPal, an American multinational financial company, was by far the most popular payment system, used by 26% of the media in this study.

Mercado Pago, a digital payment platform available exclusively in Latin America, was the second most popular, yet it is used by only 10 out of the 100 media interviewed in that region. This low level is likely because of the technical complexity of implementing Mercado Pago, as well as their relatively high fees.

Stripe, an Irish-American financial services company that is one of the most popular ecommerce solutions in the U.S., was used by just four of the media in this report. Stripe only accepts accounts from media with bank accounts in three of the 12 countries included in this study: Brazil, Malaysia, and Mexico.

To get around this challenge, some media leaders have resorted to opening a Delaware corporation in the U.S. so that they can then open a business account and qualify for Stripe. This is cause for concern because, although it’s relatively easy to start a business in the U.S., annual fees and tax filing requirements can make this a complex and expensive option.

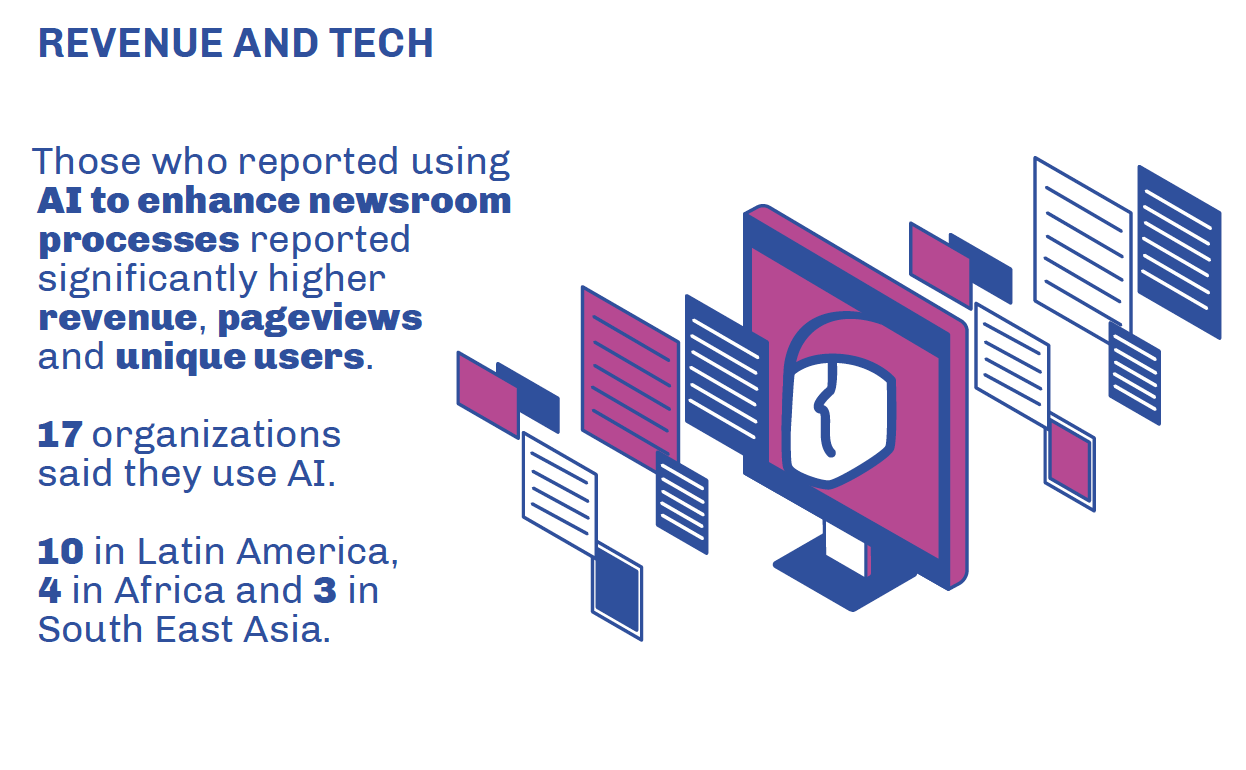

Early advances in the use of AI

Although the use of artificial intelligence (AI) was not widespread among the digital native media organizations we interviewed, those who reported using AI to enhance newsroom processes also reported significantly higher revenue, pageviews, and unique users.

About 10% said they were using AI to power content creation or enhance newsroom processes, and 12% said they were using AI bots to support journalistic content. For example, In Brazil, the legal news site JOTA is using AI to track the likelihood of bills being passed in Congress.

Sites in our sample are also using AI to support the creation of text-to-audio content. Nigerian outlet HumAngle, for example, said its text-to-audio offering broadened its audience to include those with low literacy levels and visual impairment, as well as appealing to urban readers with long commutes. Other sites are using AI to help personalize content.

AI was being used by some newsrooms to enhance newsroom processes through smart audience targeting (based on the tracking of readership and consumption trends), automated newsletter production, and interview transcription.

It is interesting to note that total revenue for 2019 in organizations that used AI to enhance newsroom processes were three times higher than for those who were not using such tools, although it is not clear from the data if this is because they were able to invest more in technology. Still, this suggests that these media organizations could benefit both in terms of resource allocation and revenue generation if they received more training on how to use basic AI tools.