Chapter 4: Digital media teams

THE STUDY

Chapter 4: Digital media teams

The digital media leaders we interviewed for this study are determined, dynamic entrepreneurs, committed to producing journalism that makes a difference to their communities, very often in challenging circumstances. But they do not do this alone. They are supported by equally dedicated teams of journalists, editors, and others.

To better understand how these media organizations operate and how the experience and structure of their teams affects their success, we studied their roles, expertise, and compensation structures.

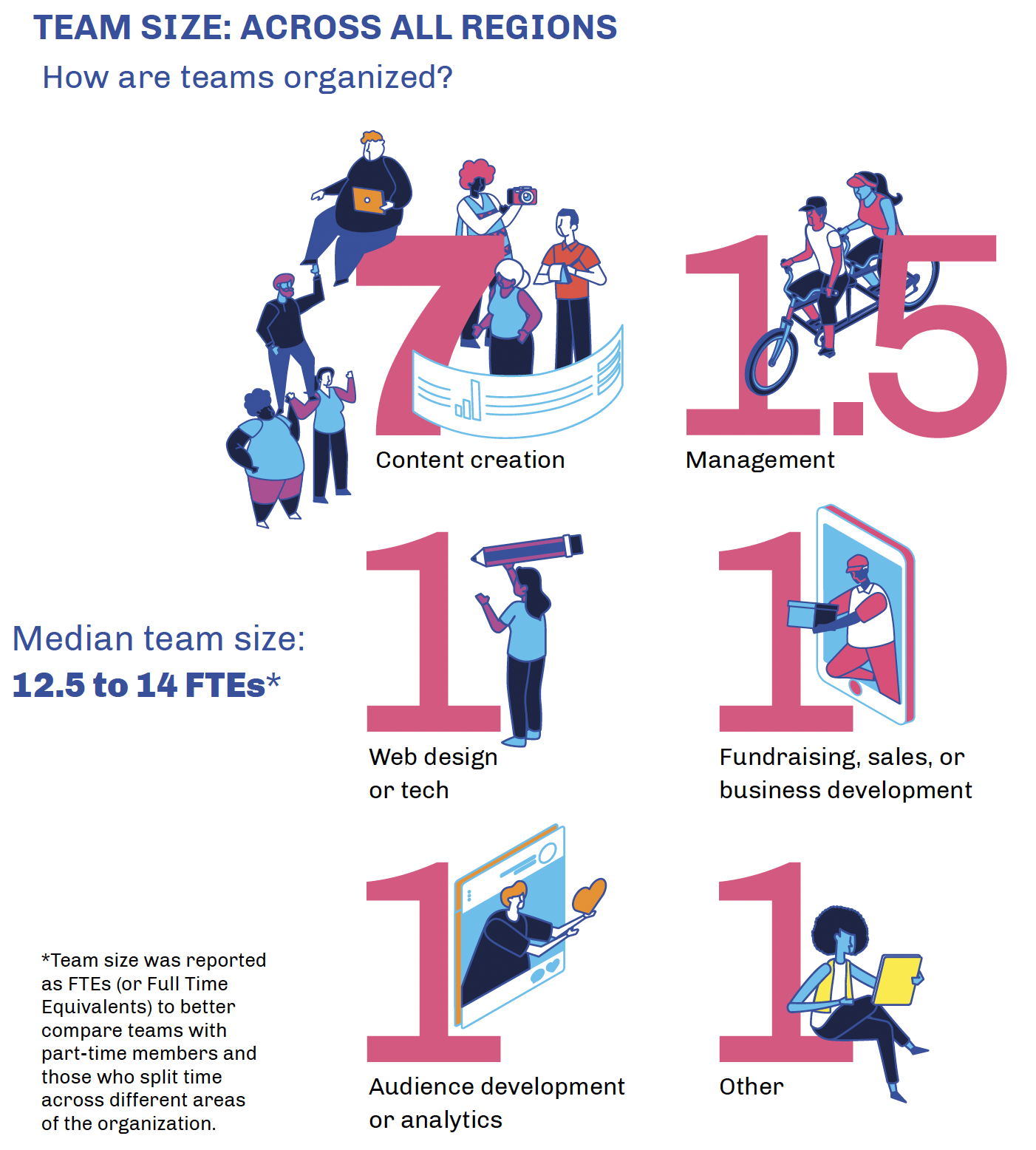

Because many of these small ventures are staffed by freelancers, volunteers, and other part-time consultants, we asked interviewees to describe their team size and specialities as full-time equivalents (FTEs). During the interviews, many of our researchers had to explain what FTE meant and had to help managers divide team member responsibilities across core categories, such as content creation, sales or business development, and finance, because in so many cases, team members wear many hats.

Across the three regions we studied, the median team size was 14 full-time equivalents (FTEs). The breakdown was: 7 FTEs doing content creation, 1.5 FTEs in management, and one FTE apiece in web design/tech, fundraising sales/business development, audience development/analytics, and other roles.

Teams with diverse skills earn more revenue

The most common challenge many of the media we studied face is that they are started by journalists with little or no business experience who primarily attract other journalists to their teams.

Yet building a team with diverse experience and skills beyond journalism dramatically increased revenue for the newsrooms we studied across all three regions.

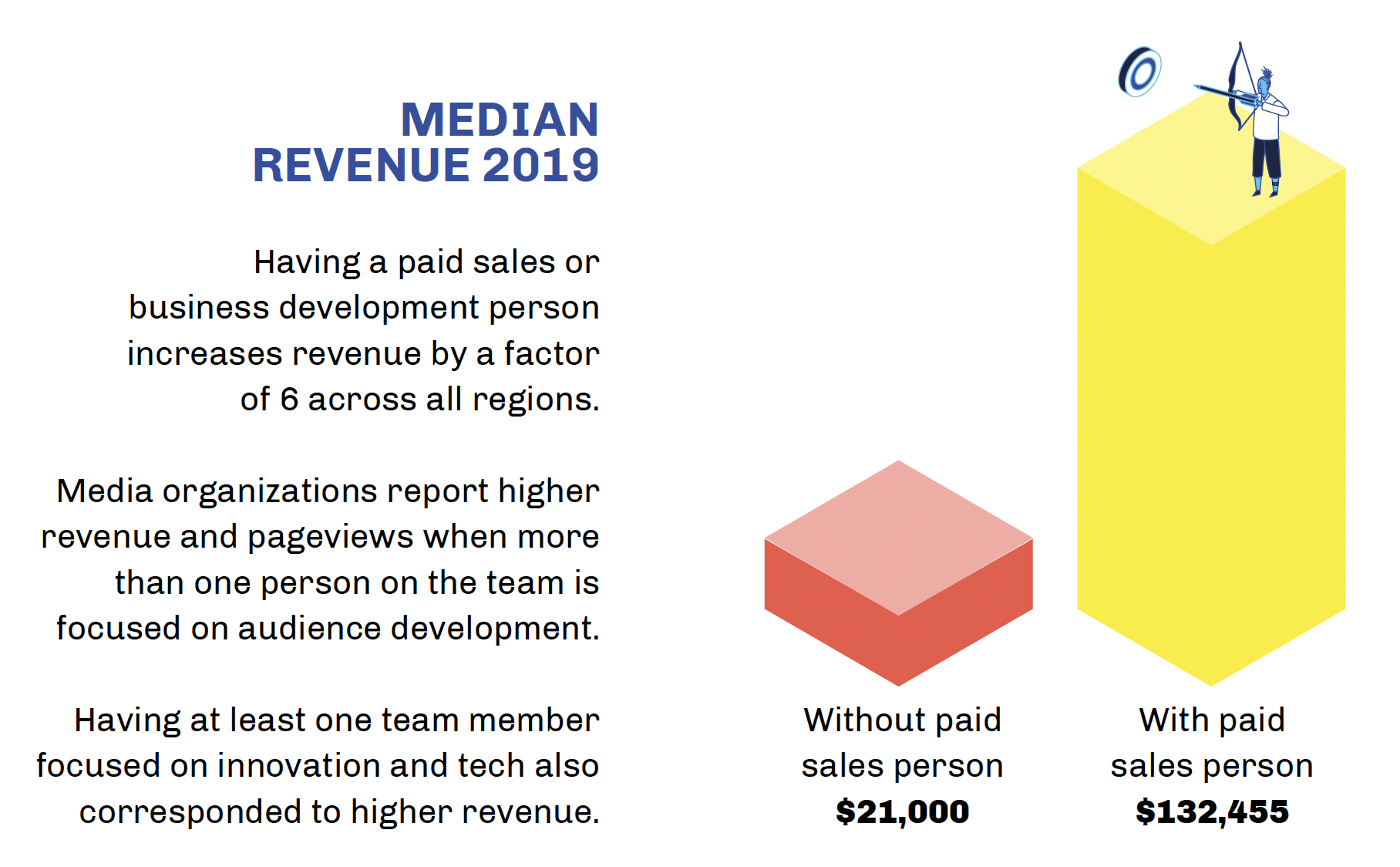

Most notably, digital native media organizations that have a paid sales or business development person on staff reported six times the revenue of those without a dedicated sales or business development person.

- The median revenue of a venture with at least one paid staff member devoted to business development or sales in 2019 was $132,455 (in our 2016 study, this figure was $117,000)

- The median revenue of a venture without at least one paid staff member devoted to business development or sales in 2019 was $21,000 (in our 2016 study, this figure was $3,900)

This finding is consistent with our 2016 research on this subject in Latin America, where we found that in the majority of the ventures, the only people raising money for the organization were the founders, and in many cases they were also the editor, manager, accountant, and more. Although it’s common for founders of startups to wear many hats, their propensity for hiring more journalists—while not allocating resources to business development, technology, and accounting—ultimately hurts their bottom line.

We were so impressed by the dramatic impact we found that a paid sales or business development staffer could have on revenue in our first study that we wanted to explore this topic further. For this study, we also asked how much these organizations pay sales people when they do hire them.

Across the three regions, salaries for sales and business development positions ranged from $200 to $2,000 a month, with a global median of $733. This expense accounted for just over 16% of a newsroom’s paid sales and/or business development expenses, on average.

Given the outsized impact of having a paid staff member dedicated to driving revenue, and the relatively low cost of labor in these markets, investing in sales and business staff members continues to provide a high rate of return on investment.

Team members with tech experience drive revenue and traffic

We also found that news organizations that paid someone to lead tech innovation reported three times more revenue—even when there were no paid sales or business development staff on the team.

After confirming that pageviews directly correlated to higher revenue, we decided to analyze which team structure seemed to attract the biggest audience. Not surprisingly, larger content teams correlated to higher pageviews, but when at least one person on the team was focused on reviewing analytics and working on audience development, pageviews were notably higher.

Founders have little experience in business, yet they are often the only ones driving revenue

When we studied Latin American newsrooms in 2016, we found that most founders had backgrounds in journalism or other social sciences. Yet they were also often the only team members working on building the business.

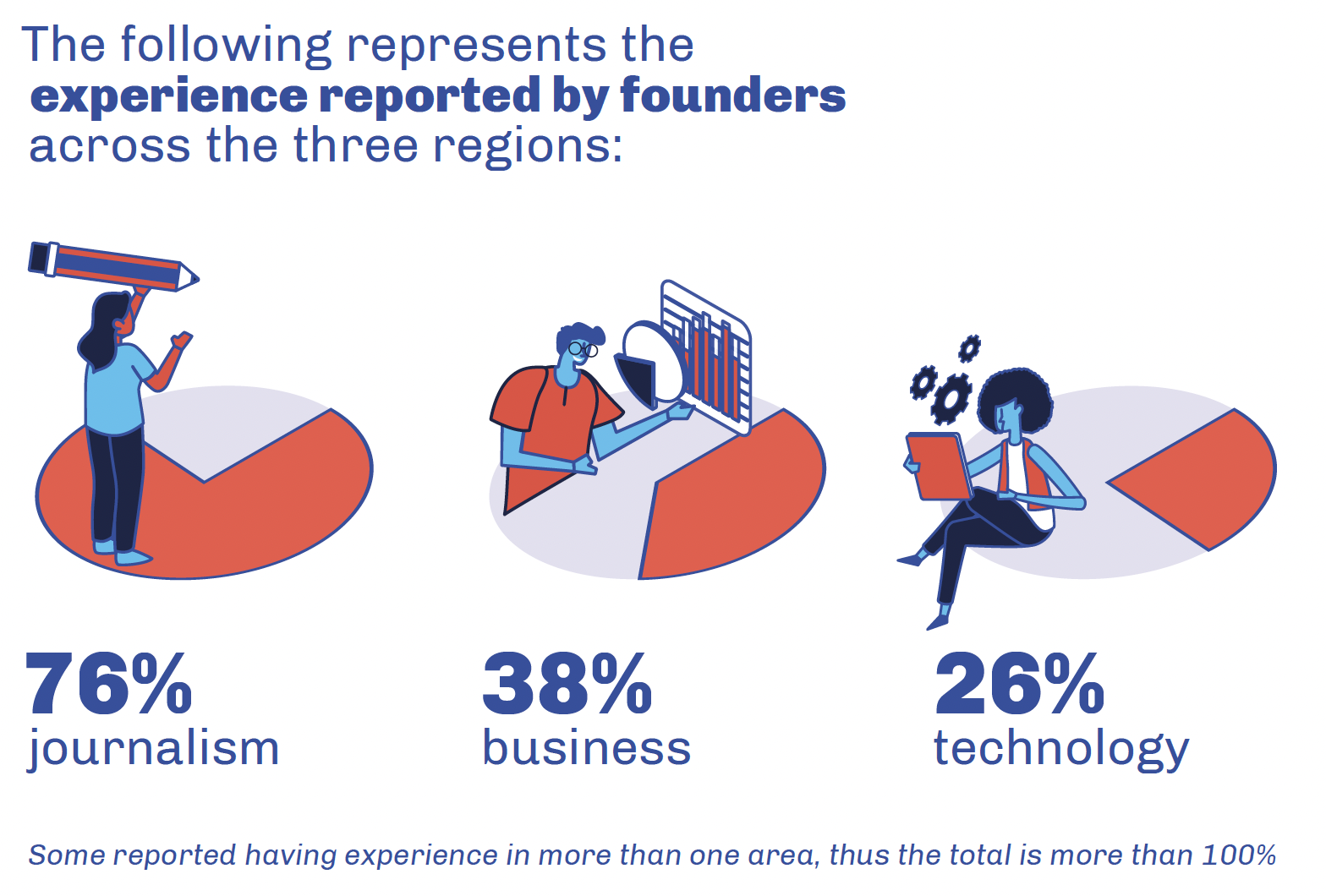

Taking a more global view this time, we found that in all three regions—Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia—more than 75% of the media leaders had backgrounds in journalism. Of those, 43% were the only ones responsible for fundraising and business development.

This finding strongly suggests the odds of success could be improved for digital entrepreneurs by providing training for existing media leaders, as well creating entrepreneurial journalism, business, and innovation courses in journalism schools to better prepare future media leaders.

Activists and journalists lead digital media in Southeast Asia

When we looked at a regional breakdown of the data on founders’ backgrounds, we found that only 44% of founders in the organizations we spoke to in Southeast Asia had a background in journalism compared to a global average of 76%. And yet we did not see a significant increase in the number of founders in the region with a background in other areas, such as business or technology.

Our regional research coordinator for Southeast Asia, Kirsten Han, pointed out that some digital native founders in the region may identify as activists rather than journalists.

When we looked at the way some of the founders we interviewed described how they served their audiences, they said things like: “Our way of activism is to combine social networking with activism,” or “We intensively report and advocate for a number of communities,” or simply “News for social change.”

High incidence of journalism fellowships among founders

Our interviews also revealed that many of these founders had participated in a journalism fellowship, media accelerator, or other entrepreneurial training program.

Notably, 37% of the media founders we spoke with had won a Nieman Fellowship to spend a year studying at Harvard, a JSK Fellowship to study at Stanford, or they had participated in entrepreneurial training programs run by the Reuters Institute, the International Center for Journalists, and others.

This finding suggests that these types of fellowships are succeeding in their goal to encourage journalists to become entrepreneurs. We did not, however, find a clear connection between these fellowships and the financial success of the media they launch.

Carlos Eduardo Huertas, founder and director of CONNECTAS in Latin America and a recipient of the Nieman Fellowship in 2011 -2012, said programs like this give budding entrepreneurs four key things: time, a fertile environment for new ideas and connections, “the language of the possible,” and the financial security to spend time exploring a new project during the program.

Women leaders

One of the most significant findings from the first Inflection Point report was that women represented 38% of all of the founders of the 100 digital native media organizations we interviewed in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico.

In our current study, we found 32% of all the founders of the 201 companies we studied across 12 countries were women.

The percentage of women leaders varied significantly by region:

- In Latin America, almost 38% of the founders of the 100 organizations we spoke with were female, the same level we found in 2016.

- When we added up all of the founders in Southeast Asia, 29% of the total founders identified as women across Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand.

- In contrast, in Africa, only 13% of the media founders we interviewed across Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa were women.

Grant support made business development possible

The motto “supporting diversity, empowering minds” runs along the top of the homepage of Indonesian site Magdalene. Founded by journalists Devi Asmarani and Hera Diani in 2013, Magdalene describes itself as a women-focused publication offering inclusive, critical, empowering, and entertaining content and perspectives.

Their dedicated work over the last eight years has earned them awards and had major industry impact: its #WTF Instagram campaign calling out sexist and misogynistic behavior at Indonesian media outlets resulted in other sites increasing coverage of gender equality. And Magdalene is often invited to present about reporting on gender issues.

But Asmarani said it was not until they began receiving significant grant funding in 2018 that they were able to start building their business and growing revenue.

“None of [the founders] knew anything about business, so for many years we were subsidizing [the site] with our own income,” she said. “We had no idea how to raise funds, our business model was nonexistent.”

Grant funding meant they could hire a full-time team, including business and community management specialists, and develop new revenue sources, including branded content, content creation, and event sponsorship.

Asmarani stressed that female media entrepreneurs in her region find it harder to secure funding, meaning they are often limited to small and medium-sized media businesses.

“Financial support is so important for organizations like us. It goes a long way in helping them go from a distressed, tiny organization into something bigger. Mission-driven, female-driven media organizations should always be one of the priorities for support for [funding] organizations.”

Diversity among digital media founders

Studying the diversity of founders and audiences across such a broad range of countries required considering different types of minorities in each country.

Many of the digital media leaders we interviewed said they were focused on reaching underserved communities in their countries. Listed in order of most frequently reported, they noted their audiences include:

- LGBTQ+ communities

- People with disabilities

- Indigenous communities

- Ethnic minorities

- Religious minorities

- Language minorities

- Other minority communities

Across all three regions, about 25% of these media organizations said that at least one of their founders represented one of these minority groups; the breakdown was nearly 30% in Latin America, 25% in Southeast Asia, and 20% in Africa.

More than 50% said they had people who identified as minorities on their teams (66% in Latin America, 48% in Southeast Asia, and 30% in Africa).

Reaching underserved communities in Nairobi, Kenya

“Tazama” is a Swahili word meaning to see, look, or observe. The founders chose this name because “seeing” and serving marginalized communities traditionally ignored by mainstream media is at the heart of Tazama World Media’s mission.

The Kenyan organization reports on and for low-income neighborhoods in Nairobi. They do this by hiring and training journalists who are deeply embedded in these communities.

Editor-at-large James Smart described what his team of nine does as “shoelace journalism.”

“Our journalists locate themselves in poor, marginalized communities and talk to those individuals as full human beings, not just people having problems,” he said. “Our reporting is trying to center the community by being with them for a period of time. They are part and parcel of this community.”

During the COVID pandemic, for example, Smart said traditional media often acted as an “echo chamber” for the government’s public health messages. But Tazama’s journalists reported on the impact that policies and restrictions were having on the low-income communities they serve.

Smart said other media did not begin to cover these kinds of stories until months after his team did, suggesting Tazama’s work provided a new feedback loop for local governments and other media organizations.

“It wasn’t that people were refusing to wear masks; they didn’t have masks. People in the markets were trying to set up water lines so they could wash their hands, but it wasn’t working,” said Smart.

Tazama World Media’s reporting from within the community not only gave them a voice but helped those voices to reach those in power to effect change. Among the results: more masks were produced and distributed, and water was supplied to local markets.

“We are trying to plug the gaps between government communication and communities receiving and acting on that communication,” he said.