Chapter 2: Media freedom & journalist safety

THE STUDY

Chapter 2: Media freedom & journalist safety

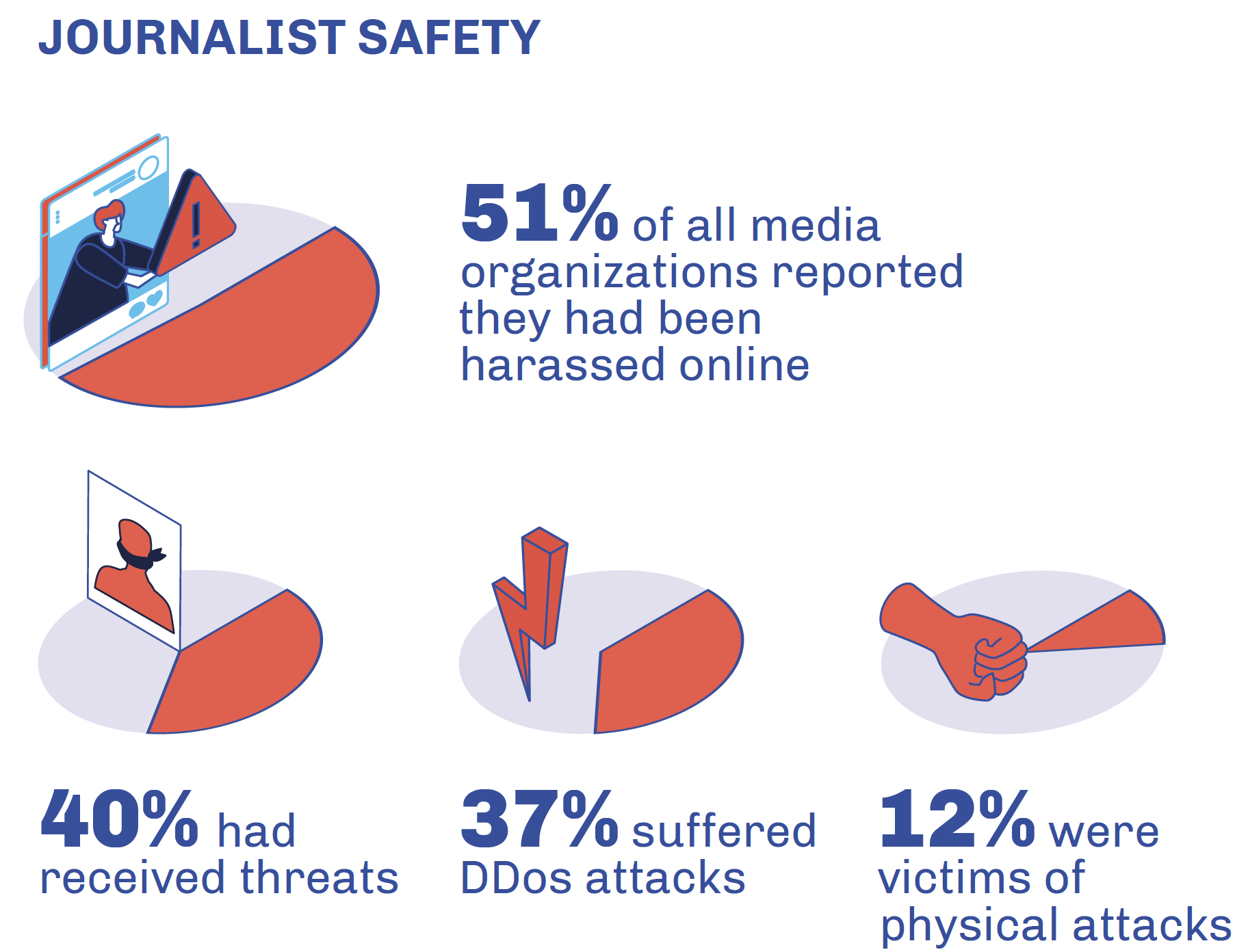

The media leaders in this report are doing their work against a backdrop of seemingly constant online attacks, threats, denunciations, lawsuits, and, in the worst cases, physical violence.

Many seemed resigned to their plight and even said they knew it was to be expected, considering the nature of their work. As one media leader said in our interview: “A certain level of upsetting people and having them make threats is part of the job.”

More than 12% reported that they or someone in their news organization had been the victim of physical violence, with almost all incidents reported taking place at the hands of the police or military while covering protests.

The majority of these attacks were against photojournalists, many of whom also had their equipment destroyed or were forced to delete their footage.

This word cloud represents the words most frequently used by media leaders when they answered questions about media freedom and journalist safety.

Digital media entrepreneurs in all but three of the “middle income” countries in this study are working in environments classified as “difficult” by RSF’s 2021 Press Freedom Index. The exceptions are Argentina, South Africa, and Ghana, whose environments are classified as “satisfactory.”

In Colombia, more than 20% of digital native media organizations reported being the victim of physical attacks in 2019 and 2020—almost twice the average for other media.

Threats and physical attacks were also reported by the media in Mexico, which is now considered the world’s deadliest country for journalists. “Nine journalists were killed in Mexico in 2020, bringing the death toll to at least 120 since 2000,” according to an article in the Guardian in 2021.

Journalists who covered hot-button issues such as human rights issues, corruption, and abortion reported the highest rates of attacks.

It should be noted that we did not include questions specifically about abortion in our interview questionnaire. However, so many media leaders said that their coverage of abortion led to a dramatic increase in threats and online attacks that it stood out in the findings.

A global study on Online Violence Against Women Journalists by ICFJ and UNESCO also found that “The story theme most often identified in association with increased attacks was gender (47%), followed by politics and elections (44%), and human rights and social policy (31%).”

LatFem coverage contributed to high turnout at demonstrations

Journalists at LatFem in Argentina covered the passage of abortion legislation more closely than other media outlets in their country. Their reporting was often cited as one of the reasons why so many Argentines participated in the massive 2018 and 2020 public demonstrations.

LatFem’s journalists covered more than 50 public debates, and participated in meetings with the Argentinian National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion. They also shared information about protests and related activities on social networks and formed alliances with other independent digital media to share coverage.

In December 2020, the Argentinian government passed legislation effectively legalizing abortion. LatFem went on to work with independent media and journalists from other Latin American countries through alliances and collaborative work, helping to foster discussions about reproductive rights that many attribute to similar legislative changes that also made abortion legal in Mexico and Ecuador in 2021.

Judicial threats and lawsuits lead to self-censorship

Across all of the media in this study, 28% said their organization had been the subject of judicial threats, but there were significant variations from country to country.

In Latin America, media organizations in Brazil and Colombia reported a much higher incidence of judicial threats—13 times more than those in Mexico and Argentina.

More than 20% of media organizations in Nigeria and Philippines reported being denounced by their governments.

In the Philippines, media leaders also said they were denounced through “red-tagging”—defined by the United Nations as “labelling individuals or groups (including human rights defenders and NGOs) as communists or terrorists,” a practice that the UN said poses a serious threat to freedom of expression.

Media in Nigeria and Ghana also reported greater frequency of lawsuits and other legal attacks than other countries in our sample.

In Africa, some media leaders said they sometimes self-censor, avoiding stories that could lead to legal challenges, because they can’t afford to hire attorneys to defend them.

“Online attacks are an everyday thing”

Said a media leader who chose to remain anonymous

Digital attacks are an increasingly common form of censorship and retaliation, and more than half of these media organizations suffered cyberattacks, ranging from hacked email and social media accounts to Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks.

Nearly all of the media leaders we interviewed reported that they or their colleagues had received threats or other types of harassment via social media in 2019. Some said they were warned that if stories were not taken down, they or their families would be at risk. The worst comments included pictures of guns and other violent images.

Some 37% reported DDoS attacks, a common method for taking down a website in which a hacker uses thousands of compromised computers to overload a website, making it impossible for anyone else to visit.

A search of the dark web reveals just how easy it is for nearly anyone to launch a DDoS attack against a competitor, political rival, or a journalist’s website. The cost of these kinds of attacks are often as low as $5 per day.

Countries where more than 50% of media experienced DDoS attacks included Philippines, Nigeria, Brazil, and Ghana. Several media organizations in these countries told us that DDoS attacks followed the publication of stories on controversial topics, such as human rights violations by police or stories about protest movements.

Notably, almost 65% of Filipino media organizations we spoke with said they had been the subject of a DDoS attack. This is the highest number of any of the countries we studied.

A significant finding was that more than half of the digital native media in this report are now using defensive software services to protect themselves against DDoS attacks, with Cloudflare reported as the most popular, followed by Project Shield (created by Jigsaw and Google) and Deflect, which is run by a Canadian nonprofit.